Beyond The Boundary:

Where have all the cricketers gone?

In part two Tom Simmonds investigates how high costs, poor behaviour and modern society have left cricket scrambling for players.

Grassroots cricket is seen by many to be the beating heart of cricket in this country. It’s where future England stars first take up the game. It’s where cricket fans up and down the country try and emulate their heroes. For others, it’s an escape, where work and other stresses can be forgotten about, at least for an afternoon.

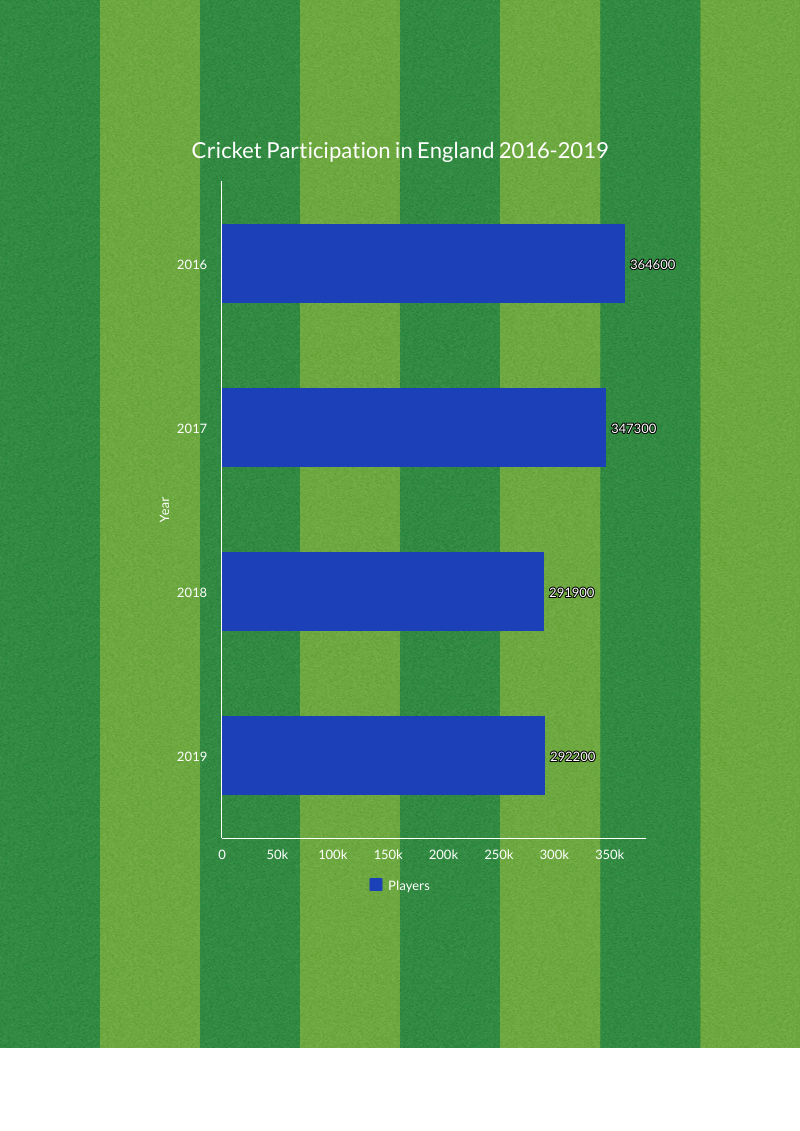

Yet it’s also got a major problem it needs to address, those people turning out every Saturday and Sunday simply aren’t turning up anymore. Cricket can no longer rely on the idea that players will always be there, teams around the country are struggling to put out full sides and whole club’s existences are being threatened. In 2016 364,600 people played cricket at least twice a month during the summer months, by 2019 that figure had dropped to 292,200. In just that short space of time 72,400 people gave up the game, cricket effectively losing over six and a half thousand teams worth of players.

Understanding why there’s been this haemorrhage is a complex issue. Factors such as a reduction in cricket on free to air television, only Channel 4’s highlights and the Cricket World Cup final were shown last year which has reduced the games standing in the public consciousness. Time issues have also contributed with people typically being busier now and unable to give up the entire day to the sport.

Yet for Simon Prodger, Managing Director at the National Cricket Conference, cost has become a major issue for prospective players: “When I started playing there used to be a team kit bag and people would dip into that but we have gone from that to now, the same as anyone who engages seriously in a recreational activity, they are looking to get what specifically suits them, almost bespoke, so the cost of a grade 1 cricket bat by a major manufacturer is so expensive.”

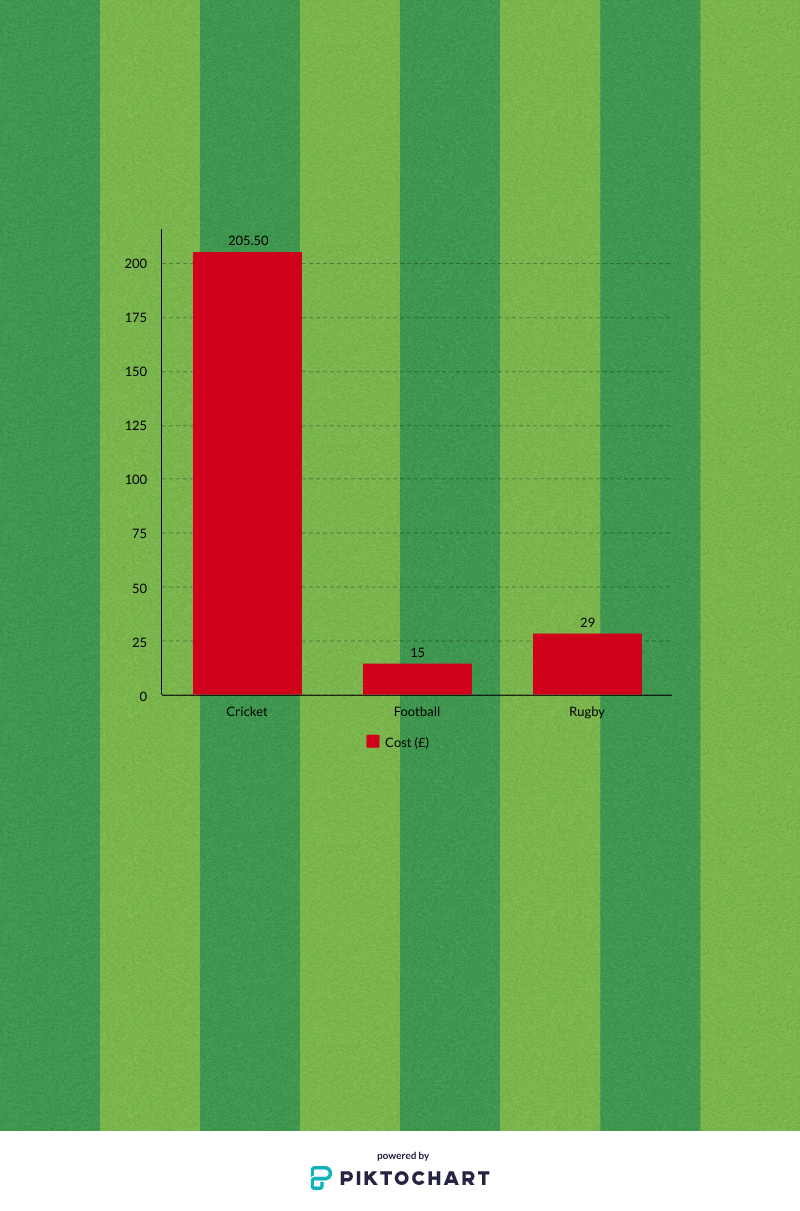

Assuming that everyone who plays the game would want their own bat, helmet, box, set of pads and thigh pads, boots and a bag to lug it all around it, we found that, even using the cheapest kit available on ProDirect Cricket, the cost of buying it all new was £205.50 and this was before you paid out for memberships, match fees, team whites or even any kit you might need for training. Using the same principle of the cheapest, necessary kit on ProDirect’s websites, neither football nor rugby even surpassed the £30 mark.

Cricket is without a doubt an expensive sport, and according to Simon Prodger that needs to be addressed: “I think the general costs of cricket for a recreational player is a major issue and I think also away from the equipment itself the costs to clubs and therefore their players is something that is having an effect on people’s decision making processes. So I think the cost is definitely a factor for amateur cricketers and it is incumbent on the game as a whole to see how it can manage those costs.”

It’s not just players that are leaving cricket. Umpires are becoming harder to find and keep whilst clubs are also struggling to attract the key volunteers they need to run effectively.

Club’s volunteers are crucial to the game whether that’s looking after the square or putting on teas each Saturday or helping the club run off the field with membership details and other admin issues. Despite their key nature, 59% of clubs have told the ECB that they are struggling to recruit these volunteers each year.

The ECB have launched their Inspiring Generations scheme which hopes to produce a new wave of volunteers and double the number currently involved in the game although the effects of it have yet to be felt.

It’s no secret that cricket is struggling with umpires, many leagues now only provide a standing umpire each week with some even admitting they are struggling to have enough to even manage to send an umpire to every game, instead having to rely on the club’s to find a volunteer or hope that players will be fair enough to officiate their games themselves fairly.

According to Simon Prodger, the sport only has itself to blame for this:

“I think over the last 5-6 years the level of discipline in cricket has been abysmal. We are involved in offering arbitration at the end of individual leagues disciplinary processes and there has been some shocking incidents. I wouldn’t want to umpire in league cricket and I think also not just the disciplinary but the expectations of umpires from cricket itself have increased, you know the umpires are now liable for making decisions that directly affect individuals or clubs in terms of whether it's safe to play or not, and as we becoming increasingly Americanised in our society here we are getting into areas of litigation and potentially legal issues.

“I think all of these things are making people think twice about how much they want to be an umpire in league cricket and an awful lot of umpires are only doing friendlies, wandering teams and school cricket by choice and not doing league cricket any more.”

Despite this, there are bright hopes for the future. Tim Mansfield, an umpire in the Westmorland League is optimistic “We’ve worked hard over the last 6 months to recruit umpires. We had 9 registered for the stage 1 course in January and 11 for stage 2 and player behaviour is overwhelmingly good in our league.”

The exodus of players appears to be slowing too, 2019 bucked the decreasing trend and actually saw an increase from 291,200 in 2018 to 292,200.

Russell Perry, chair of the Northumberland Cricket Board, believed that before the COVID-19 situation, 2020 would have been a key year for the game saying: “The year ahead is pivotal to the game. We all wait to see the impact of the 100 and its impact upon attracting new players and supporters. We have a five-year window on which to secure the game’s future and build on the foundations already in place.”

John Windows, Academy Director at Durham Cricket, believes that the club’s decision to pull the academy out of the North East Premier League will only help the strength of club cricket in the region: “To strengthen or to continue to help our players continue their development in clubs is one aspect of it and to maintain their playing strength so it didn't make sense to starve clubs of their best young cricketers when they'd all be playing leading roles for those teams.”

In short cricket's heyday of the last century may be well behind it and with society now being very different to that of yesteryear, it may never get back to those levels of importance.

But despite this there's plenty to suggest at the very least grassroots cricket's look set to continue at its current level for some time to come and who knows if the England side continues its eye-catching successes of 2019 they may just inspire a new generation.

It won’t be straightforward but as Tim Mansfield put it: “There probably isn’t an easy solution. Hopefully its cyclical and the next generation will put aside their tablets and VR toys and take part in the greatest game in the world!”